Before 9/11

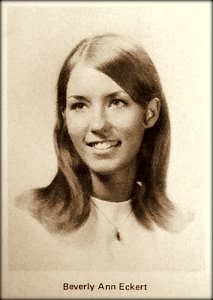

Beverly Ann Eckert was born May 29, 1951 in Buffalo, New York. She ran and skipped and bicycled her way through her early years, like any other kid. But there was something about her that set her apart: she was determined to write the story of her life even when faced with hardship and sacrifice.

She grew up in Eggertsville, NY, a few miles from Buffalo, and attended St. Benedict School from kindergarten to grade 8. Beverly had a brother, Raymond, and three sisters: Susan, Karen and Margaret (Margot). When Bev played with her siblings and friends she was not just one of the pack. She excelled and she led. Bev could “out-bike, out-dodgeball, and out-hide-and-seek the neighborhood gang,” as Margot wrote in her poem, “Strong Woman.” Bev was active, creative and gregarious — jumping rope, building forts, dressing up like a cowgirl and getting swept up in the Mickey Mouse Club fad as a Mouseketeer.

Beverly excelled during her high school years at the Buffalo Academy of the Sacred Heart, an all-girl school sponsored by the Catholic Sisters of St. Francis. Teachers and friends saw she had an artist’s eye, a writer’s ear, and the passionate heart of a true romantic. At Sacred Heart, her classmates called her Bev, and she wrote poetry, drew pictures, acted in plays, shone on the basketball court and took a turn at student politics. Her friends and teachers noticed she had a certain flair, a talent, a drive. What Beverly wanted to accomplish, she did. And like so many young people rushing toward adulthood, Bev wanted to fall in love. One of her best friends, Kathleen DeLaney, described how Bev eagerly counted down the days to her fifteenth birthday, and on May 31, 1966 joyously announced: “I can date!”

Then she went to the dance that changed her life. In the fall of 1967, Bev met Sean Rooney in a crowded Buffalo high school gym. Sean was a thin young man with thick, curly, dark hair and a bright smile that warmed those around him. Soon they began to date, but it was not a fairy-tale romance the whole time. There were rough patches, as on any road, with parental troubles and heartache. When Bev’s mother said she could not see Sean, she did not listen. And upon her 18th birthday, in 1969, Beverly left home, supported herself as a waitress, and endured hunger and exhaustion so she could follow her heart. “It was a real struggle to make ends meet,” she had said. “Okay, so the right to date whomever you want isn’t exactly in the Constitution,” she added, “but ever since that time I haven’t been afraid of adversity or the consequences… of standing up for what I believe in.”

As the years passed, the financial struggles continued, but Beverly at least had a stalwart partner in Sean. She started her studies as an art major in 1969 at SUNY College at Buffalo (now known as Buffalo State). She and Sean moved in together two years later, and as their love and commitment grew they bought a two-family house together in 1973. In 1975, after six years of full-time work and part-time studies Bev got her Bachelor of Arts degree. In addition to her coursework, she had put in long hours at AM&A’s Department Store, Mother’s Bakery Restaurant, and the Sign of the Steer Restaurant and Bar, where Sean also worked. For a couple years after graduation Beverly worked as a potter, selling her wares at art shows and by word-of-mouth. Then began her career in the world of insurance, with a job at Travelers Insurance, first in Buffalo in 1978, and then at branches in Massachusetts.

On June 14, 1980, in a simple ceremony in the back yard of her sister’s home in East Aurora, NY, Beverly Ann Eckert married Sean P. Rooney. The high school sweethearts had become college loves and then wife and husband. They were so close in life and in the minds of their relatives and friends that they became SeanandBev, one word, one love, one life. Oh, such a love. They never had children, but loved their nieces and nephews and the children of their friends. They were partners in building a life together, in feathering each of their nests. He cooked, she cleaned, and they both worked hard at their day jobs. And at the end of a hard day, Sean would walk through the door and say to Bev, “Where’s my hug?” And Bev would remember: “Sean was a good hugger.” Food was always important, and in the kitchen Sean was in charge while Bev offered a hand and a glass of wine, whichever was needed. After a good meal, they would sit together and talk quietly and be thankful for the comfortable life they had made for themselves.

In her working life Beverly was strong and determined, pushing firmly against a culture of ingrained sexism. She said that women were not permitted in the corporate dining room of Travellers Insurance when she first arrived at the company. “What I experienced throughout my insurance career was life as a minority, an outsider, often the only female at a meeting or in the room.” Despite this, Beverly rose through the ranks, becoming a vice president and manager at Gen Re, a reinsurance company. “I can say I had a successful career,” she said, “but it was seldom comfortable. I had to respect myself in an environment that seemed to want me to feel otherwise, just like when I was poor.”

For their 50th birthdays in the year 2001, they did something special. Beverly and Sean gave each other the gift of travel. She chose Morocco for her birthday, and he chose Vermont for his. But no matter where they were, it was in each others’ company that they were the most fully contented. Beverly said how happy they had become with their lives that last summer they spent together in their Stamford, Connecticut home. Beverly said she was sitting with Sean at the back door one evening, drinking wine and watching the fireflies come out. And Sean said that if he’d died right then, it wouldn’t be so bad, because he’d lived such a good and full life.

After 9/11

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Beverly Eckert was frantic to learn the fate of her husband once she heard the news that the Twin Towers were hit by terrorists flying airliners. When Sean’s voice at last reached her over the phone, she had a moment of elation, thinking he had made it out of his burning skyscraper. But her world was quickly shrouded in blackness. Sean told her he was still in the South Tower, and his way out was blocked by wreckage and a hellish blaze. She knew at once that her one love would not leave the building alive. Sean and Bev said their goodbyes, their final “I love yous.” As Sean drifted from consciousness, Beverly heard the sound of destruction and death on the phone. Then silence.

Beverly Eckert vowed she would not be dragged into a morass of grief over what she had lost, but instead celebrate all that she had. And this she did just days after the tragedy, organizing a memorial service in the Buffalo area, and willing herself to be the strong one, the one others leaned on. And in just a couple of weeks she was behind her desk at work, pressing on with her busy career as an insurance executive. But she had also become part of a new group: those who lost a loved one on 9/11.

This group was large and diverse, but it faced a long and perplexing list of common challenges. How to deal with the grief, with the recovery of the remains, making ends meet, dealing with the various social services, government agencies and other groups that wanted to help the family members? Beverly Eckert lived her post-9/11 life with the same strength and determination that marked her earlier years. But a new side of her emerged as well. She would now become a leader.

Beverly Eckert was one of the founders of Voices of September 11th, an organization which helped 9/11 family members and others obtain reliable information about such matters as counseling and other social services, financial assistance from relief groups and government agencies, and the identification of remains. With her professional experience in the fields of insurance liability and compensation, she also took the lead in monitoring and critiquing the 9/11 Victim’s Compensation Fund.

The 9/11 attacks were carried out by a band of determined, cold-blooded zealots. They were guilty of mass-murder on a scale unprecedented in the United States, successfully carrying through a terrorist plot more destructive than anything before it. But as the weeks after this horrific calamity turned into months, 9/11 family members began to ask questions. They began to wonder whether their loved ones had to die. Was the visa system as secure as it could be? How could men armed with box cutters pass through airport security and take over four airliners? Did first-responders have all the tools they needed to save lives at the crash sites? Were the Twin Towers designed and built to the best standards? And where were the vaunted and massively funded intelligence services in all of this, the largest failure on their part in recent history?

A number of family member groups arose in order to answer these and other questions, and to find ways to fix what was clearly a number of broken systems. While most of Beverly Eckert’s energies were devoted to Voices of September 11th, she was also involved in groups dealing with the Victim’s Compensation Fund, airline security, skyscraper safety, a memorial at Ground Zero, and the handling of remains.

In 2002, however, she began to spend more time on one of the biggest questions: What were the government’s failures before, during and after 9/11, and how could these be fixed in order to prevent future attacks? Beverly Eckert and other 9/11 family members coalesced around this cause, supporting the efforts of a number of senators and members of Congress. The first step was to establish an independent commission to investigate government failures.

Beverly Eckert and her colleagues were instrumental in the creation of the 9/11 Commission, through tireless lobbying, mobilizing the support of other family members and the general public, and spreading their message through the media. Once the commission and its staff began a massive investigation, Beverly Eckert and twelve other family members (constituted as the Family Steering Committee) forcefully made their questions and concerns known to the commissioners and staff. They pushed for honest, open answers to tough questions from anyone who had useful knowledge, all the way up to the president.

Once the 9/11 Commission issued its final report, Beverly Eckert and other members of the Family Steering Committee, and other family activists, used their newly gained political expertise and influence to prod Congress into passing legislation based on the report’s recommendations. After tough battles in the centers of political power, Beverly Eckert and her colleagues stood up to the Pentagon, the Speaker of the House, and the President himself. The most powerful forces in Washington were arrayed against them, but they did not know they had no hope bending them to their will. And so they won. The major achievement of the family members and their legislative allies was the largest reorganization of this country’s intelligence services since the dawn of the Cold War in the 1940s.

Once this great hurdle was crossed, Beverly Eckert took some time off from her lobbying and advocacy work. She spent some time sailing warm waters, visiting tropical islands, recharging her batteries, renewing her soul.

When she returned from this break, Beverly Eckert embarked on the next chapter of her life, one devoted mostly to service. She tutored elementary school children, taught senior citizens to draw, and built homes with Habitat for Humanity. She also pressed issues related to 9/11. She was part of a group of family members working on non-proliferation of WMDs. And she joined other family members in a meeting with President Barack Obama at which she gave him a letter outlining her view that terrorism suspects should not be held at Guantanamo Bay, but brought to trial on U.S. soil.

A few days later, Beverly Eckert was en route to Buffalo, where she was going to present a scholarship she established at Canisius High School in Sean’s name, and to celebrate the birthday of the man she loved and lost. A few minutes before the plane would have touched down at the Buffalo airport, her plane stalled, lost speed and control, and fell on top of a house in a fireball.

Sean never made it home from work on September 11, 2001. Beverly never made it to Buffalo on February 12, 2009. But the two of them left behind a story of deep love, a love that transcended the evil and pain of 9/11, and rippled outward in countless acts of kindness, principled activism, and selfless service.

Awesome story!! So sad both of their lives were so short.

This is so sad theirs life were cut short God Bless Them Both

Thank you so much for sharing this beautiful story. It’s one I have not heard before. I too grew up in Buffalo New York. I now live in my parents home, the one I was raised in. Every day I am so thankful for the memories that this brings! The story of 9/11 has always been incredibly important to me. Every year I watch The tributes on TV. My heart goes out to this loving couple. Sad as their deaths were, I’m so thankful they are together once again in heaven!